In November 1905, a young scientist by the name of Dr Kurt Hessen travelled from Bremen, Germany to Western Australia on the vessel “Scharnhorst” to conduct research of international importance over several years in suburban Bayswater. What was this work? Was this German national in fact a spy? And what tragedy was to befall Dr Hessen while he was still in Western Australia? One of the files held in the State archives collection holds the clues to this gripping story.[1]

As the earth rotates on its axis, it actually wobbles. This small deviation was documented in 1891 by American astronomer Seth Chandler and has since become known as the “Chandler wobble”. An international program to measure the degree of wobble was established in the late 1800s. Although Wikipedia would have you think the United States established such a program, observatories were erected across Germany for measuring the Chandler wobble prior to the commencement of American observations. These observatories were known as International Latitude Stations and were progressively set up across the northern hemisphere. Only two such stations were established below the Equator: one in Argentina, the other in Bayswater Perth.

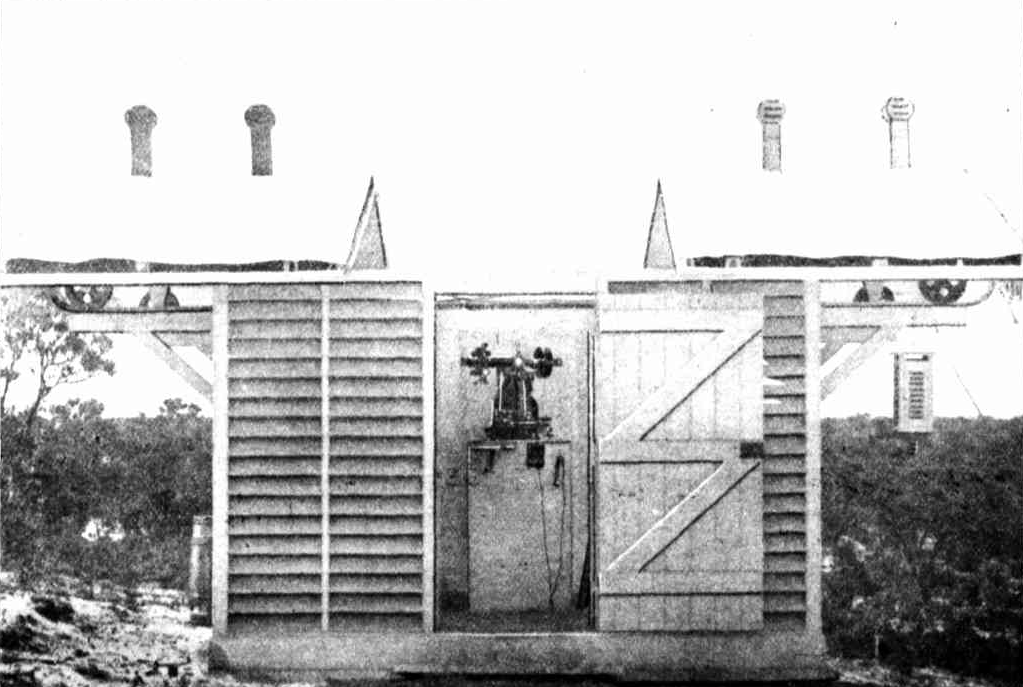

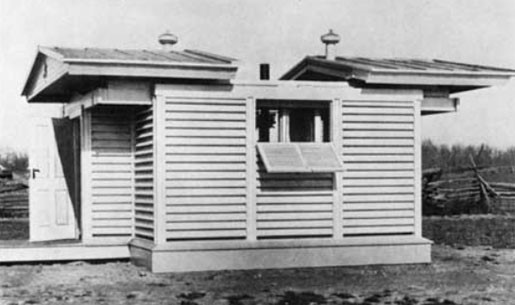

Why Bayswater was chosen for such a station is not fully known, other than being at the required latitude. The availability of the land, its proximity to the Perth Observatory and its good elevation are likely to have been factors. The observation site was at the corner of Hamilton and Stations Streets, Bayswater. The site remains a small public reserve to this day although it is largely unused as a children’s playground with no recognition of its historical significance. The scientific research carried out on this site appears to be a bit of overlooked history.

Dr Hessen, second assistant at the Berlin Observatory, commenced his night-time observations of the stars on 6 January 1906. Dr Hessen lived close to the Bayswater observatory and would no doubt walk, or perhaps cycle, there each evening to conduct his work. He was well known in the Perth scientific community and, obligingly, also conducted latitude observations for the Department of Lands and Surveys when required. At that time, the Department established temporary latitude stations in places such as Wanneroo, Laverton and Onslow to conduct nocturnal calculations but for local survey / chart related purposes, rather than as part of the broader international project. One Departmental file notes the observations Dr Hessen provided to the State government “found that positions given in the (commonly used) nautical almanac were not good”.

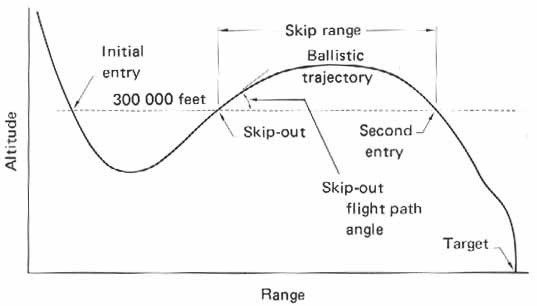

The data compiled by Dr Hessen as part of the international project was provided to the International Geodetic Society in Berlin which received information in a similar form from other Latitude Stations across the world. As well as being of immediate practical benefit (e.g. to navigators), the data collected by these stations remain of use to scientists today, including for research into polar motion and climatology, and for satellite tracking. NASA continues to use this data for helping to calculate the re-entry of space vehicles.

Dr Hessen concluded his scientific observations in mid-1908 and was due to return overseas in February 1909. However, the day before his departure, he shot himself in the head with a revolver at Lake Monger. Amazingly, Dr Hessen survived. As the West Australian reported in sensational fashion on 10 February 1909, a local groundsman: “saw the man … with one hand clasped to his mouth, and the other gripping a smoking revolver”. Police and medical assistance were sought at once. Obviously in intense pain, Dr Hessen could still relate to the groundsman what he had just done. The newspaper goes on to report: “(Dr Hessen) is a distinguished scientist and in professional and other circles in the city has, since his arrival from Germany about three years ago, been extremely popular”. The article states that on the previous weekend a hearty send-off has been provided to Dr Hessen by his many friends at the Perth Club and “there was nothing … which would give … the slightest indication that so tragic an occurrence was impending”.[2] Dr Hessen was only 27 at the time of this incident.

Dr Hessen recuperated for several months at Perth before returning to Germany. Information provided to the writer by the Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam states that Dr Hessen continued scientific work (tidal observations) at Wilhelmshaven, that he was a master of the piano and that he died at the relatively young age of 49 after a short illness. It appears Dr Hessen never married.

The circumstances behind Dr Hessen’s attempted suicide remain a complete mystery. Was it an overwhelming desire not to return overseas, or perhaps a local romantic interest that had gone wrong?

Soon after WWI, in deliberating what to do with the Bayswater observatory, a government official wondered: “… one is apt to wonder whether these German observers were sent out all over the world solely in the interests of science, or if espionage was not one of their chief duties”.[3] The inference that Dr Hessen may have been a spy of some sort appears completely incorrect.

The Bayswater observatory fell into disrepair and was dismantled in 1923, its part in a major international scientific project 100 years ago almost forgotten.

Reprinted with permission from Damian Hassan, Senior Archivist, State Records Office of Western Australia